Getting into classrooms doesn't mean impinging on the autonomy teachers need to do their jobs. Here's how leaders can pay attention to practice without micromanaging.

By Justin Baeder, PhD

Are Classroom Walkthroughs “Micromanagement”?

While our model for classroom walkthroughs shows great respect for the work and thinking of teachers, many teachers have had negative experiences with classroom walkthroughs.

Over on Facebook, someone named Marc commented that our Classroom Walkthrough Tracker was a “Micromanagement Tracker.”

Marc isn't totally wrong here—micromanagement is a real problem in K-12 schools, and it's among the most common drivers of teacher turnover at the building level.

Teaching is professional work that requires a degree of autonomy to exercise professional judgment.

Teachers know this, and bristle at being both micromanaged and expected to exercise professional judgment.

As leaders, we can't just ignore teacher practice and leave everyone on their own, but we need to approach supervision in specific ways that are respectful of the professional nature of teaching.

What Self-Determination Theory Says About Autonomy & Job Satisfaction

Self-Determination Theory, one of the leading frameworks for understanding human motivation, identifies three factors that are central to intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction:

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

- Competence

If teachers experience classroom walkthroughs as a barrage of criticisms and directives, it's no wonder they don't appreciate the attention from leaders. Such approaches are direct assaults on teacher autonomy and competence.

Given the choice between being left alone and being subjected to unsolicited advice and judgment, most teachers would prefer to be left alone—and this is indeed a commonly expressed sentiment: “Just let me teach!”

But those aren't our only two options. We can choose among four basic approaches to instructional leadership.

The Micromanagement Matrix

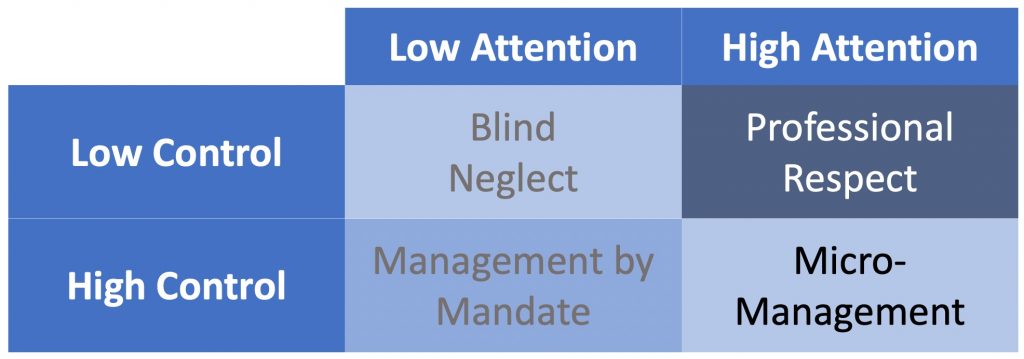

If we plot the amount of attention instructional leaders pay to teacher practice on one axis, and the amount of control they attempt to exert over teachers' decisions on the other axis, we get the following 2×2 matrix:

© The Principal Center

The most common approaches are those that don't require leaders to spend much time in classrooms:

- Blind Neglect, or as teachers often put it, “being left alone.” This may be what people say they want, especially if they've never worked with supportive administrators. But it leaves administrators in the dark about teacher practice, resulting in decisions that aren't based on evidence about what teachers really need.

- Management by Mandate, in which administrators issue directives that impinge upon teacher autonomy, without getting into classrooms to see for themselves what teachers and students are experiencing.

In both of these cases, administrators' lack of firsthand knowledge about teacher practice leads to decisions that are disconnected from classroom realities.

On the other extreme, spending ample time in classrooms can give leaders an abundance of valuable insight into teacher practice, but this insight must be coupled with restraint.

- Too often, leaders fall into micromanagement, second-guessing teachers' instructional choices and giving unsolicited feedback that teachers perceive as intrusive.

- It's only when leaders resist the urge to micromanage, and instead show professional respect for teacher autonomy that we get the best of both worlds—valuable decisional information, without taking away the autonomy that teachers both crave and legitimately need.

Learn how to get into classrooms the right way: take the Instructional Leadership Challenge »

Why Teachers Need Autonomy To Do Their Jobs

Why is autonomy so important, beyond its role in motivation and retention?

As Charlotte Danielson explains in her excellent book Talk About Teaching, teaching is intellectual work:

If one acknowledges, as one must, the cognitive nature of teaching, then conversations about teaching must be about the cognition.

Charlotte Danielson, Talk About Teaching: Leading Professional Conversations, (2nd Edition), p. 7, 6

Teaching entails expertise; like other professions, professionalism in teaching requires complex decision making in conditions of uncertainty.

Listen to Charlotte Danielson discuss her book on Principal Center Radio »

If teaching is intellectual work that requires rapid-fire decision making, micromanagement cannot succeed.

To micromanage is to take upon oneself the responsibility for decisions that should be made by the teacher. If leaders succeed in usurping teachers' decision-making role, they will quickly be overwhelmed with an untenable number of questions.

Teachers make perhaps 1,500 decisions per day, according to EdWeek. Deferring to administrators on even 1% of these decisions would bombard them with hundreds of questions each day, many of which require immediate answers.

Unsurprisingly, teachers don't readily submit to micromanagement, and have a wide range of strategies for resisting it.

Perhaps the most common is to simply acquiesce to administrators' demands enough to be left alone, while continuing to do what they think is best the rest of the time:

“Oh, thank you for the feedback. Yes, I'll be sure to try that.”

Others may push back, advocating for their own perspectives and raising objections to feedback they don't agree with.

But in the most extreme cases, teachers can react to micromanagement by simply quitting.

We must find ways to help teachers grow without taking away the autonomy they need.

Learn how to have feedback conversations that change teacher practice: download 10 free evidence-driven questions for better feedback on teaching »

How To Improve Teaching Without Micromanaging

Teachers want leaders' attention, but without giving up control of their classroom decisions.

Let's be honest: this is hard for leaders who care about quality instruction and want to “fix” anything that could be better.

It's hard to spend a lot of time in classrooms and not develop an urgency for improving everything that's subpar.

But here's the thing: all improvement must happen through teachers' professional judgment, not in spite of it.

We can only improve teaching by improving teacher judgment—not by taking it out of the equation.

“Do what I tell you” is micromanagement or management by mandate.

And frankly, teachers get whiplash when we lurch between blind neglect and micromanagement and mandates.

Successful leaders in high-performing schools that keep and grow their teachers long-term know that the only real option is that top-right quadrant of the matrix above: professional respect.

This respect is manifested in our approach to classroom walkthroughs.

When we engage teachers in respectful, evidence-based conversations about their practice, we'll have opportunities to sharpen their professional judgment—both in the moment and longer-term through professional development, budgeting, strategic planning, and other high-impact decisions leaders make.

But if we engage in top-down, boss-knows-best walkthroughs that make teachers feel like they can't do anything right, we're veering into micromanagement.

One thing we must stop doing: giving the feedback sandwich.

Why The Feedback Sandwich Undermines Teacher Autonomy

Everyone has experienced feedback of this sort:

- First, a compliment, designed to establish rapport and reinforce effective practice

- Second, a suggestion for improvement—the “meat” of the sandwich. Inevitably, this suggestion has an embedded criticism, and the implication that the leader knows best.

- Third, an additional compliment, to cushion the blow of the criticism and end on a high note.

This is the kind of feedback we hear from the judges on reality competitions:

“I liked your energy on stage, but you were a little pitchy during the chorus.”

This judge-centric model of feedback does not translate well into the education profession, for several reasons.

- In most cases, the teacher did not ask for feedback, and certainly not feedback on whatever specific issues we may choose to address. Unsolicited feedback is rarely appreciated.

- When we observe teaching, we're seeing just the tip of the iceberg. 90% or so is hidden beneath the surface and not directly observable. Reducing teaching to visible behaviors ignores its cognitive nature—a danger we call Observability Bias.

- Giving suggestions, rather than engaging in conversation, impinges on teacher autonomy.

So what can feedback look like, if it doesn't involve the feedback sandwich?

As Danielson suggests, the answer is conversation.

Read: Classroom Walkthrough FAQ for Instructional Leaders »

Questions for Feedback Conversations that Preserve Teacher Autonomy

Rather than ask leading questions like “Have you thought about…?” that are really suggestions in disguise, it works best to ask open-ended questions that get the teacher talking, but that start with specific evidence from your visit.

Here are 10 evidence-driven questions you can use—simply share [something you noticed] when you see [ ]:

- Context: I noticed that you [ ]…could you talk to me about how that fits within this lesson or unit?

- Perception: Here’s what I saw students [ ]…what were you thinking was happening at that time?

- Interpretation: At one point in the lesson, it seemed like [ ]… What was your take?

- Decision: Tell me about when you [ ]… What went into that choice?

- Comparison: I noticed that students [ ]… How did that compare with what you had expected to happen when you planned the lesson?

- Antecedent: I noticed that [ ]… Could you tell me about what led up to that, perhaps in an earlier lesson?

- Adjustment: I saw that [ ]… What did you think of that, and what do you plan to do tomorrow?

- Intuition: I noticed that [ ]… How did you feel about how that went?

- Alignment: I noticed that [ ]… What links do you see to our instructional framework?

- Impact: What effect did you think it had when you [ ]?

Download as a PDF: 10 Questions for Better Feedback on Teaching »

A Complete Walkthrough Model

In Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, I recommend making 3 classroom visits a day that are:

- Frequent—18 biweekly visits per teacher per year

- Brief—around five to fifteen minutes

- Substantive—more than just making an appearance

- Open-ended—focused on the teacher’s instructional decision-making, not just narrow data collection

- Evidence-based—centered on what actually happens in the classroom

- Criterion-referenced—linked to a shared set of expectations

- Conversation-oriented—designed to lead to rich conversations between teachers and instructional leaders

These 7 elements (Chapter 2 of Now We're Talking!) will get you into classrooms long-term, while keeping you from falling into micromanagement.

Read: Classroom Walkthrough FAQ for Instructional Leaders »

Take the Challenge & get Now We're Talking Hardcopy + Audiobook »

Have other questions? Leave a comment.

Leave a comment below if you have other questions about classroom walkthroughs.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for student learning

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs.