What are mental health days, how do they align with district policies and professional norms, and how should school leaders address them?

First, let's talk about the time-tested professional norm for sick days, and why it's been disrupted in recent years.

The Golden Rule for Sick Days

Educators have long used an implicit professional norm to govern sick days:

If you need to take a sick day, take it.

If you don't need to, don't take one, because taking a sick day you don't need may prevent someone else from taking a day they do need.

This Golden Rule applies equally to physical and mental health, and no one should have to justify their decision to take a sick day, except perhaps when there's evidence of misuse.

This Golden Rule is powerful as a professional norm, because it allows large numbers of people to coordinate their decision-making and behavior without close oversight. There is no need for administrators to police or second-guess individual teachers' decisions.

Take a day if you need it. Don't take one if you don't.

What does it mean to “need” a sick day? In recent years, we've expanded our definition of “need” to encompass earlier intervention. For example:

- If you come down with a cold, take a sick day as soon as you realize you're sick—don't wait until you're sick as a dog and can't work

- If you're about to hit the wall mentally, take a day to reset—don't wait until you snap at someone or have a full-blown anxiety attack

These are good and much-needed adjustments to our collective thinking about sick days. We've lowered the bar for taking a sick day, and this is a good thing—for too many educators, it's been too high.

Because the Golden Rule is such a powerful norm, many experienced educators are reluctant to “take a day” unless they absolutely cannot work, like Barbara on Abbott Elementary, who reluctantly agrees to take a mental health day at the urging of a district counselor.

Leaders are encouraging teachers to take sick days more preventatively, before there's an acute problem.

This is generally a positive development, but it's complicated by uncertainty and ambiguity about when, precisely, it's OK to take a sick day.

When large numbers of people are operating under a common norm, but apply it very differently, we encounter the problems we're seeing today.

Who Pays The Price for Unfilled Absences?

Ideally, educators should be able to use their sick days when they need them, based on their own judgment.

If everyone gets, say, 10 sick days a year, they should be free to use them as needed without it being anyone's business.

Sick days are a district expense, and sub coverage is a district responsibility—not something teachers should have to worry about when they're sick.

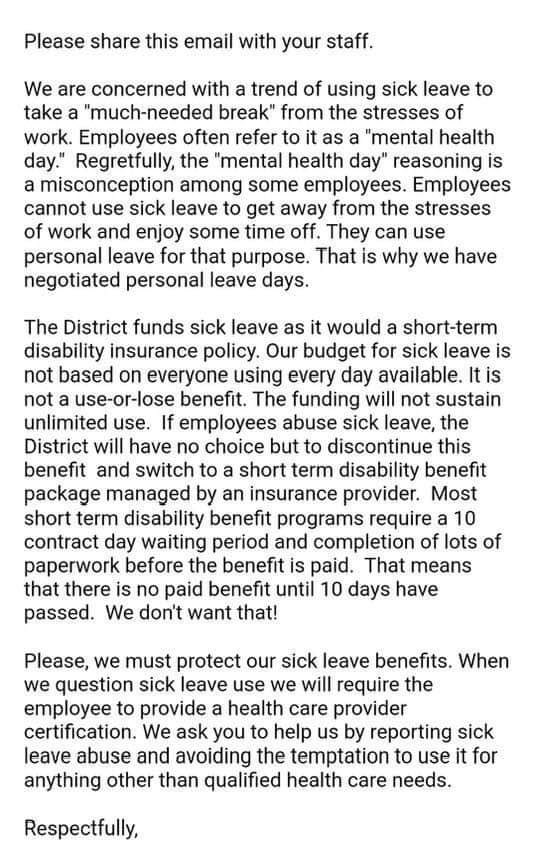

This internal memo from an unnamed district recently created an uproar when it made the rounds on social media:

Commenters rightly pointed out that none of this is the individual teacher's problem—teachers should be free to use their sick leave without worrying about how it's funded.

But there's another dimension to consider as we seek to make the Golden Rule a bit more flexible: what impact will an absence have on one's colleagues?

Ideally, none—again, teachers should be able to use their sick leave without guilt and without worrying about anything other than getting well.

In some contexts, there are enough subs, and it's not a problem. People are generally exercising good judgment about using sick leave, and it's not resulting in unfilled absences.

In some schools, though, subs are scarce, and absences frequently go unfilled.

Unfilled absences have only three solutions:

- Administrators and other staff can cover classes

- Teachers can cover each other's classes during their prep periods

- Classes can be combined, with one teacher supervising twice the usual number of students (or more)

In many schools—perhaps most—these are rare occurrences. In six years as an elementary administrator in Seattle Public Schools, I only had to cover a class for one day.

When I was a middle school teacher, though, unfilled absences were common. I can't count the number of times my colleagues and I were called upon to cover classes during our prep periods.

Today, after a pandemic and years of assaults on the dignity of the teaching profession, unfilled absences are a daily reality in many schools.

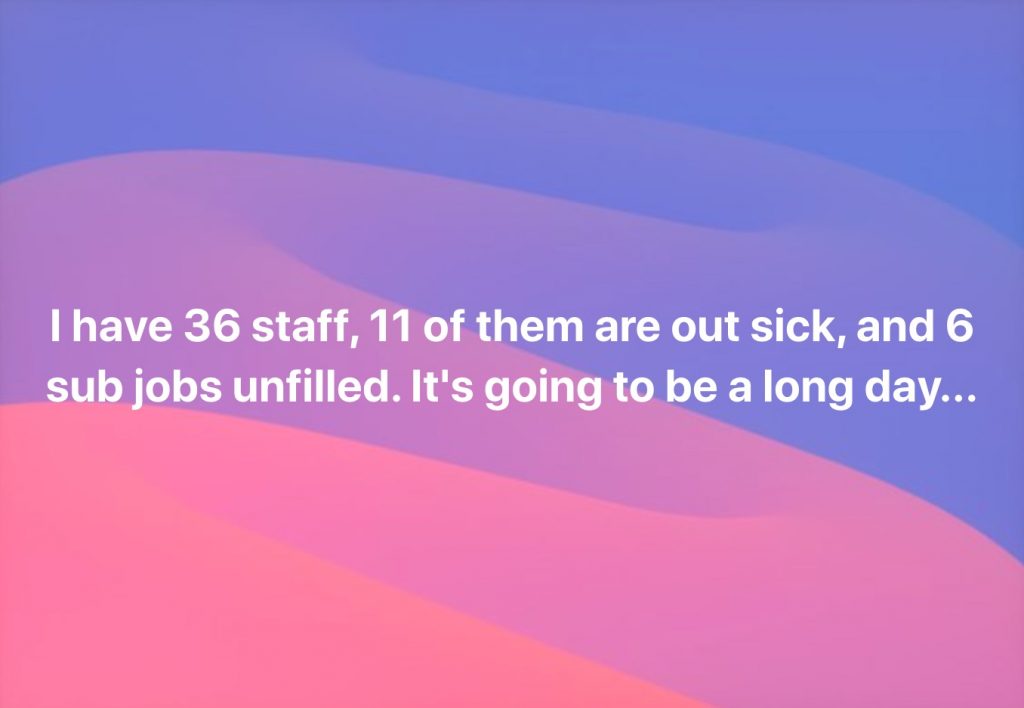

One principal shared their reality on social media in late 2022:

I would certainly rather cover a class myself than have someone try to work while sick, and virtually all administrators and teachers would do the same.

But one principal physically cannot cover 6 unfilled absences, which means teachers will be called upon to give up their prep periods.

It also means that instructional coaches, counselors, interventionists, and anyone else who isn't already teaching class all day will be forced to suspend their duties in order to cover classes.

In such cases, taking a sick day doesn't just incur a cost to the district. It incurs a cost to colleagues and students, too.

Now, most educators would again say “That's OK. Take the day if you need it.”

We take care of one another in this profession. We look out for one another.

But if we're all operating from wildly different understandings about what level of need justifies a sick day, conflict is inevitable.

It is profoundly unfair for teachers with a higher bar to constantly cover classes for people. who have no self-imposed threshold for using sick leave.

Again, most of the time, we defer to one another's judgment and don't second-guess anyone's decision to use a sick day.

But a quiet crisis is brewing, and it's the unintentional consequence of our own desire, as leaders, to be flexible and compassionate toward teachers who, frankly, all need a break.

How High Is Your Bar For Using Sick Leave?

I truly believe our desire to be flexible about sick leave is well-intentioned.

No administrator wants to give teachers a hard time about using their sick leave as needed. We want to be empathetic and flexible.

But different people will interpret the same message very differently.

Consider three groups with differing standards for when to use sick days:

- High-bar teachers, who will only take a sick day if they absolutely cannot work

- Medium-bar teachers, who will take a sick day when they need it, but not when they don't

- Low-bar teachers, who will take a sick day regardless of any specific need on that particular day, in the name of general wellness

High-bar “Barbara Howard” teachers will do whatever it takes to show up every day, and will gladly cover for their colleagues—even at great personal cost. In a strong school with a veteran staff, the majority of teachers may feel and act this way.

For generations, teaching has been seen as a selfless career in which personal sacrifice is noble and expected—even to a fault.

As leaders, we need to encourage our high-bar teachers to lower their bar a bit, and to take sick days when they need them. We also need to encourage them to say no to covering classes and taking on other extra work when they don't have the bandwidth.

Medium-bar teachers are quickly becoming the norm. They take sick days when needed, and help others maintain healthy boundaries around work. They are glad to cover for colleagues who need a sick day, but also know their own limits.

I believe medium-bar is the healthy balance we need to strive for as we adjust the Golden Rule, but there are some key points of confusion around mental health, which we'll address in a moment.

Low-bar teachers see their sick leave allotment as an entitlement to use without reservation. They see no distinction between PTO (or “personal days”) and sick leave, and do not hesitate to use sick leave for personal errands, rest, and relaxation.

Low-bar teachers—and administrators, like Abbott Elementary's principal, Ava—take their days without any regard for the impact on others.

Let's be clear: low-bar thinking violates both the letter of most district sick leave policies, and the spirit of the Golden Rule.

Low-bar thinking is unethical, inconsiderate, and, depending on the specifics of one's contact, may even be considered fraud. (We'll consider evolving PTO policies below.)

Historically, low-bar thinking has been rare. Bad actors have been few and far between, and easy to deal with on an individual basis.

But at this moment in the history of our profession, we're actively encouraging people to adopt low-bar thinking, with profound unintended consequences.

Shifting The Burden To The Most Selfless Teachers

A new generation of teachers is entering the profession without the high-bar tradition of sacrifice. They see teaching as a job in which they need to fight for acceptable working conditions, not a calling that demands total self-sacrifice.

This is a long-overdue shift. Ending the exploitation of teachers—paying them fairly, treating them as professionals, and ensuring healthy working conditions for everyone—is an urgent priority.

But whenever we're adjusting longstanding professional norms, we must proceed with great caution, or our most selfless teachers will bear the brunt.

The sick leave crisis is unfolding before our eyes:

- Leaders are encouraging self-care and increased use of sick leave

- Newer teachers are taking the message to heart and using more of their sick days—a mix of medium-bar and low-bar, with fewer high-bar norms

- Veteran high-bar teachers are still reluctant to use sick leave, but even more willing to cover for their colleagues, now that leaders are encouraging lowering the bar

- As a result, the most selfless teachers are giving up prep periods to cover classes, day after day, even when they can least afford the added stress

This is a classic Shifting the Burden dynamic from systems thinking, in which the stress of one group of teachers is systematically transferred to another group.

Leaders have an obligation to protect our most self-sacrificing teachers from overburdening themselves out of concern for their colleagues.

Traditionally, the Golden Rule—take a sick day if you need it—has handled this problem.

But when norms are evolving, leaders must be more intentional about aligning expectations across different groups of teachers.

Rather than second-guess individual teachers' decisions about using sick leave, we must address this challenge with greater clarity about where to place the bar.

A simple mantra leaders can use—the Golden Rule:

If you need to take a sick day, take it.

If you don't need to, don't take one, because taking a sick day you don't need may prevent someone else from taking a day they do need.

But what does “need” mean?

Defining “Need” for Sick Days

If people are uncertain whether they need to take a sick day, the operative question is “Do you need it now, or can it happen another time?”

If I was up half the night with an anxiety attack, but it's over now…do I need to take a sick day? Probably so—I'll need rest before I can teach effectively. Sleeping in on Saturday won't meet the need.

If you have a doctor's appointment, does that justify a sick day? Of course—most doctor's appointments can't be scheduled for non-school hours.

But vague language about about wellness and mental health obscures the fact that much of what people might do on a personal day does not rise to the level of need that justifies a sick day.

The best way to calibrate our thinking on this matter is to consider physical health and mental health in parallel.

For example, exercise and healthy eating are essential for physical health. That does not mean, though, that it's acceptable to use a sick day to work out and do meal prep.

Exercise and cooking are important-but-not-urgent personal tasks to do on personal time, not emergencies that can only be taken care of during the school day.

Some respondents on Twitter said they'd feel fine about using a sick day as a mental health day to catch up on personal errands, because it would make them feel less stressed and more ready to face the challenges of the workday.

If a teacher is sufficiently stressed that they're unable to function, then of course it's well past time to take a sick day.

Like exercise and cooking, though, personal errands that contribute to one's overall well-being can be done on personal time. They don't need to happen during the work day—therefore, they're not an appropriate use of sick leave.

This is true whether we call a day off a “mental health day” or a sick day—sick leave is only for needs that must be met immediately, and can't be taken care of later.

Just as we're all responsible for maintaining our physical health in our personal time, and only using sick leave when it's necessary, the same applies to mental health.

We must also address the delicate topic of mental health head-on.

Mental Health Days vs. “Mental Health” Days

Society is far more open about mental health today than just a few years ago. Younger educators talk about taking mental health days without any sense of shame, and increasingly, veteran educators do, too.

De-stigmatizing mental health makes it easier to talk about staying well, whether physically or mentally. This is a good thing.

When it comes to sick leave, there's no distinction between physical and mental health needs.

Both are equally valid, and always have been.

We need to make sure all teachers get the message loud and clear: If you need a sick day for your mental health, take it—just as you'd take a sick day if you had the flu.

In years past, educators who needed a mental health day may have resorted to a white lie in order to protect their privacy and dignity—for example, saying “I have a migraine” rather than “I feel like a panic attack is coming on.”

Health information is intensely personal, and people are entitled to a degree of privacy about their reasons for using sick leave.

As it has become more socially acceptable to talk about mental health, more educators are being transparent about their true reasons for using sick days, and that's a good thing.

But our openness to talking about mental health is a double-edged sword. If we're not careful, openness can give way to disingenuousness, and acceptance can give way to trivialization.

There is a difference between a mental health day and a nudge-nudge, wink-wink “mental health” day. One is justified by legitimate need; the other is a vacation day posing as a sick day.

Now, let's be clear: only the individual knows the difference. This is a matter of professionalism, not policing.

As leaders, it's not our place to grill teachers about whether their mental health days are “real.”

But it is our job to uphold strong professional norms. We need to reinforce the Golden Rule—take a sick day if you need it, but only if you need it—and align expectations around the middle bar.

If we don't, low-bar teachers will take advantage of sick leave policies, at the expense of the high-bar teachers who can least afford to cover for them—and no one will be able to say anything.

Is this a merely hypothetical problem? How can we tell if this is actually happening?

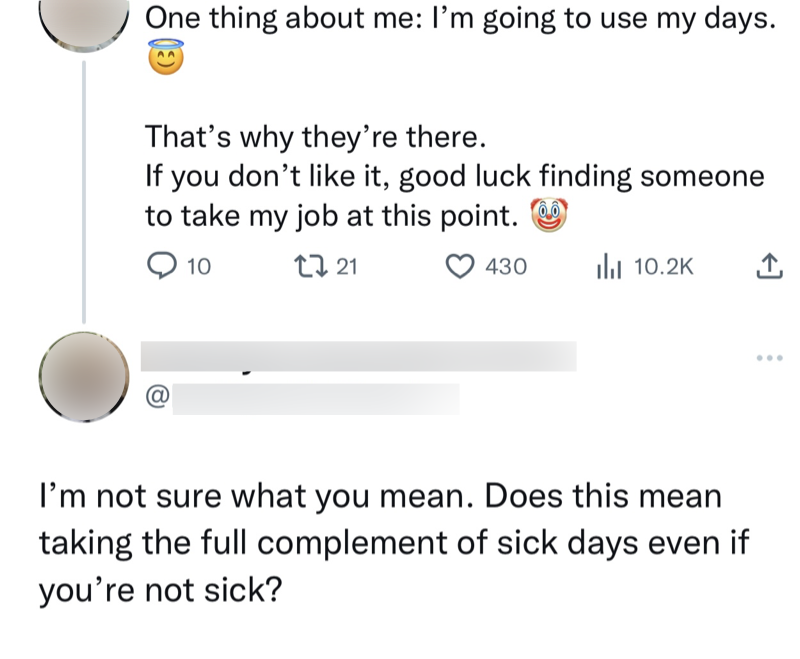

Surprisingly, people are being quite clear about what they're doing.

Teachers Are Openly Boasting About Taking Sick Days They Don't Need

Personally, I find it deeply offensive when people invoke “mental health” disingenuously.

Mental health is real and serious, and deserves to be taken seriously—not as an excuse for taking vacation days on school days.

There's a difference between normalizing discussion of mental health and trivializing mental health.

In 2018, WeAreTeachers published an article entitled “Should Teachers Take Mental Health Days?”

That article, and others like it, opened the door to much-needed discussion around mental health, but these discussions have obfuscated the question of need.

Does everyone need a break? Does everyone need rest? Absolutely.

Does that erase the distinction between sick days and personal days?

Not so fast.

Having a general need does not necessarily mean addressing that need during the school day.

Low-bar teachers have been increasingly vocal about their entitlement to use sick leave without regard for need:

I've been seeing this attitude for years, and while I could care less about the cost to the district, I know that in many cases, it's high-bar colleagues who will pay the price.

Take It If You Need It, And Spend It How You Please

Mental health is health, and it's perfectly legitimate to take a sick day if you need it.

And if someone needs to take the day off, what they do with their time on that day is their business. For example, this teacher on TikTok took a mental health day and went shopping at Target.

She's under no obligation to stay at home or do anything in particular. It's her time.

But it's wrong to take a sick day unnecessarily. It's a violation of the Golden Rule that has served our profession for generations.

As leaders, it's our obligation not to police individual sick days, but to uphold this norm.

This seems to be the point of the greatest confusion due to differing definitions: what exactly is a mental health day?

Three Types of Mental Health Days

There are at least three ways people use the term mental health day:

- Low-bar mental health days: days that low-bar educators take simply to relax or deal with personal business, as the district memo above describes.

The term “mental health” is used in a lighthearted and deliberately vague manner, with a strong implication that there was no particular need that prompted the day off, nor is it anyone's business to question its legitimacy.

Medium- and high-bar educators do not use sick days in this manner. - Medium-bar mental health days: days that educators take when they recognize a need to prevent further deterioration, like this teacher who “needed a reset” and had a dentist appointment.

(She says she took a personal day, but most districts would consider this a perfectly valid use of sick leave.)

Typically medium-bar educators will take these days, but high-bar educators will find it difficult, and need encouragement from leaders to take care of themselves. - High-bar mental health days: days that educators take when they are dealing with an acute issue that makes it difficult or impossible to work, such as a panic attack, severe depression, or an anxiety attack. High-bar educators may take sick days only reluctantly, even when it's clearly needed.

People have widely varying personal standards for what level of need justifies a mental health sick day—some see no need for a reason at all, while others feel so guilty about taking a day of sick leave that they try to come to work even when fully incapacitated.

As a profession, we must clarify this issue.

We must confront the lack of professionalism in low-bar thinking.

In many cases, teachers with higher levels of need are covering classes for absent colleagues who had no particular reason to be absent, but just wanted to take a “mental health” day.

The Responsibility of the System

Districts bear responsibility for recruiting and retaining substitute teachers .

Post-pandemic, many school systems found themselves scrambling to hire substitutes, and were slow to increase compensation enough to close the gap.

This may not be the individual's fault, but if we know our colleagues will bear the brunt of our decisions, it's hard not to mentally raise our bar.

As school leaders, we need to actively remind high-bar teachers that it's OK to take a needed sick day without worrying about how it'll be handled.

As system leaders, we need to make sure every school has enough subs.

And perhaps it's worth rethinking the sick leave vs. personal leave distinction.

Rethinking Sick & Personal Leave

Some districts are talking about combining sick leave and personal leave into a single bank of days, e.g. PTO (Personal Time Off).

This approach is widely used in the private sector, and it's what we do at The Principal Center for our employees—we don't distinguish between sick and vacation and other personal leave.

In public school districts, it's far more common to provide separate banks of sick days and personal days, and there's a reason.

As the insensitive memo above indicates, school districts budget for personal days, but do not actually budget for the full cost of all allocated sick days.

Low-bar educators may say “Not my problem!” and treat this as an opportunity to fight back against an uncaring, impersonal bureaucracy.

But if there aren't enough subs to go around, their colleagues pay the price.

As a leader, you can advocate for better sick leave policies, including greater acceptance of mental health as a valid reason to use a sick day.

But it's also important to help employees understand why sick leave works the way it does.

How much sick leave a person needs varies greatly from employee to employee.

As a new teacher, I was shocked at how much sick leave I received—far more than I could use. Of course, my situation was not everyone's:

- I didn't have kids at the time

- I didn't have elderly relatives to take care of

- I didn't have a chronic illness

- I was never hospitalized, and didn't have many regular doctor's appointments

Sick leave allotments will always be more generous than some people need, and not nearly enough for others' needs.

That's equity—doing what we can to give everyone what they need, even if it's not precisely equal.

Healthier people with fewer dependents won't get to use all of their sick days.

If we insist on absolute equality, forcing everyone to take the same number of days, some won't have enough, and some will have more than they really need.

On the other hand, personal days (or PTO) are typically allocated equally to everyone, since they're not based on need.

Some districts are also adding no-questions-asked “mental health” days to teacher contracts, which are functionally the same as personal days.

Why not treat all sick leave as personal leave? Two reasons:

- For a given budget, people would get fewer total days, because personal leave costs more (since people use it all).

- As a practical matter, allowing people to take 10+ days off per year regardless of need is unworkable due to sub availability.

Let's look at how the Golden Rule balances the demand for subs, and why abandoning it will make sub coverage unmanageable.

How The Golden Rule Balances Demand for Subs

Low-bar thinking—that it's OK to take a sick day even when you don't need to—may not seem to be a problem, as long as it's relatively rare.

As new teachers enter the profession and adopt low-bar mindsets, though, we face a growing problem.

With each passing year, as more high-bar teachers retire and are replaced by low-bar newcomers, the number of sick days used—and when they're used—will change dramatically.

Among the high-bar teachers, sick day usage will vary according to concrete factors in the physical world—such as their personal health (both physical and mental), the health of family members they care for, and doctor's appointments.

Let's say they use 40% of their days on average, and these days will be distributed based on real-world factors like illness and doctor's appointments.

Among the low-bar teachers, sick day usage is simply a matter of personal preference, and they use every day they're allotted.

What's going to happen as the high-bar group shrinks due to retirement, and the low-bar group grows due to new hires?

If you're saying to yourself “The district's going to have to budget more for sick leave,” you're right, but that's not the point.

That's not the crisis that's brewing, because money can be moved around.

The real problem is staffing those absences with actual human subs—districts will need more subs in the coming years…but that's still not the real problem.

The real problem is the distribution of those sub days.

When people take sick days based on need, their usage reflects real-world events like doctor's appointments, panic attacks, and the flu.

When sub usage doesn't reflect phenomena in the physical world, and is just a matter of individual choice, there's no natural limit on how many people can call in sick on any given day.

And when are people going to feel like using those days, if usage is not driven by need?

Even with strong, longstanding norms against calling in sick on Mondays, Fridays, and before and after breaks…it's always been a problem.

If those norms evaporate, this becomes a full-blown crisis.

If teachers get 10 sick days and two personal days per year, in a 36 week year, that means using one day every three weeks.

Spread out evenly, that's not a problem. But if even a fraction of the staff takes their days on a Friday before a break—in addition to the people who are actually sick—staffing become impossible.

This may feel like a distant, hypothetical concern, but it's the reason we have the norms we do, and we abandon them at our own risk.

In the more immediate term, the reason to take a sick day when you need it, and not when you don't, comes down to the Golden Rule.

What Do You Think?

If you have thoughts on mental health days and sick leave, leave a comment or tweet @eduleadership, or email me at [email protected].

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for student learning

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

Dr. Baeder is the co-author, with Heather Bell-Williams, of Mapping Professional Practice: How to Develop Instructional Frameworks to Support Teacher Growth. His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs.

Being a teacher is a very stressful yet fulfilling job because they are molding the future of the kids however teachers should take good care of themselves. I strongly agree that it is important for teachers to take care of their mental health and well-being, just like any other profession. Sick leave for mental health days can help prevent burnout and ensure that teachers are able to provide the best possible education for their students.

Prioritizing our mental-wellbeing is crucial. Let’s build a supportive environment where we acknowledge and handle everyone's mental health with compassion and consideration.

We only get ten days total, must be nice to get twelve. It's just not enough. I have severe arthritis and pinched nerves and allergies. Ive suggested that our union fight for more days, but it goes unnoticed. I always run out and then get docked.