Free Resources from The Principal Center

The Principal Center does not sell any programs or offer any paid services on school discipline.

It has come to our attention that many researchers, activists, and vendors are making inaccurate claims and giving bad advice about school discipline.

In an effort to provide sound guidance to educators and policymakers, this page contains all of our resources on discipline, authored by Director Justin Baeder.

All resources are provided free of charge, and Dr. Baeder does not accept paid speaking engagements on these topics.

New: Best Practices for Eliminating Cell Phone Use During The School Day

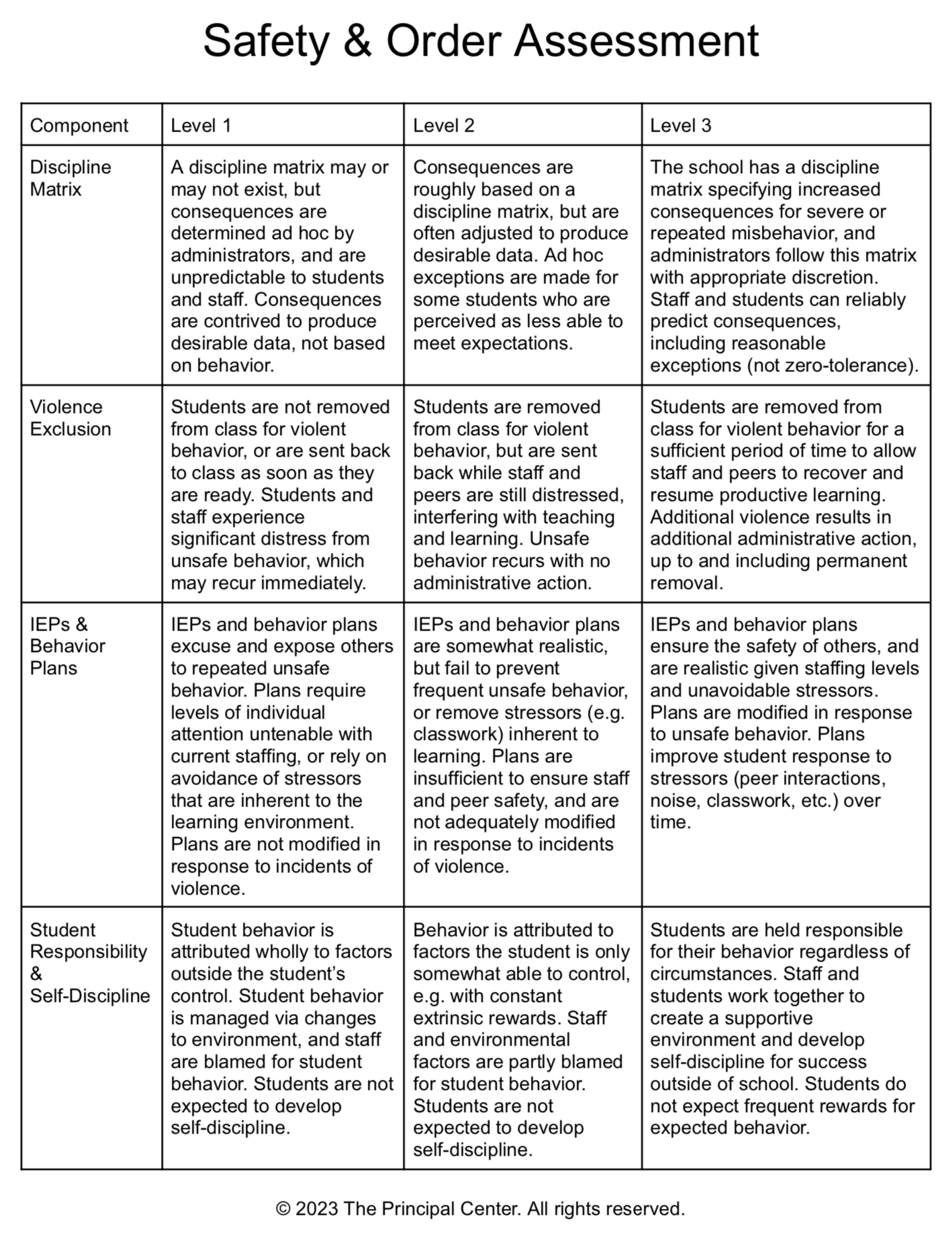

School Safety and Order Assessment

Struggling to retain staff due to violence and injuries?

This 4-part school self-assessment allows you to rate your school on 4 critical dimensions:

- Progressive Discipline Matrix

- Violence Exclusion

- IEPs & Behavior Plans

- Student Responsibility & Self-Discipline

Table of Contents

Overview: What Is Progressive Discipline?

- Progressive Discipline (PD) is the only viable approach to school discipline because it protects the rights of students while protecting the learning environment from violence and disruption.

- Every school must have a clear, published discipline matrix specifying consequences for specific categories of behavior, such as classroom disruption, fighting, and assault.

- Consequences need to be "progressive," meaning increasing in severity for repeated or more serious misconduct.

- Administrators must exercise sound professional judgment to make discipline decisions based solely on the school discipline matrix and the facts of the situation, not based on the specific students involved.

- While some students may need differentiated supports, it is not appropriate to differentiate consequences in violation of the school discipline matrix.

- Flexible, ad-hoc approaches to discipline may sound appealing as a way to address individual circumstances, but they have serious drawbacks that make them inappropriate for school discipline.

- Unpredictable consequences create confusion about acceptable behavior, and encourage students to take their chances with bad behavior.

- A lack of predictable, progressive consequences for behavior makes other students feel unsafe—especially students who have experienced trauma or have been victimized by others.

- Teachers become frustrated when they perceive inconsistency in how serious discipline issues are handled—especially when students are returned quickly to class after a major incident.

- Using an obviously ad-hoc approach to discipline undermines a leader's legitimacy, and makes students, parents, and staff less supportive of discipline decisions.

- Giving different students different consequences for the same behavior violates students’ rights to equal protection under the 14th Amendment.

- Consequences under PD are predictable, moderate, progressive, and applied with sound professional judgment.

- Predictable consequences help students regulate their behavior, feel safe, and trust the legitimacy of school leaders.

- Moderate consequences provide accountability without the discouragement that can result from excessively harsh consequences.

- Progressive consequences ensure that the same behaviors cannot disrupt the learning environment over and over with no change.

- Consequences applied by leaders exercising sound professional judgment avoid many of the pitfalls of suspension bans on one extreme, and zero-tolerance policies on the other extreme.

- Other approaches to school discipline create substantial liability for organizations and leaders.

- Giving different consequences for the same behavior violates students' right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment, which applies to local officials including school administrators.

- Failing to use progressive discipline creates liability in cases of staff or student injury that were reasonably foreseeable based on previous behavior.

- Informal attempts to address behavior without progressive consequences tend to be viewed from the outside as evidence of inaction.

- When students ultimately face discipline for severe behavior issues, the lack of prior progressive consequences makes it difficult to respond adequately.

Using A Progressive Discipline Matrix

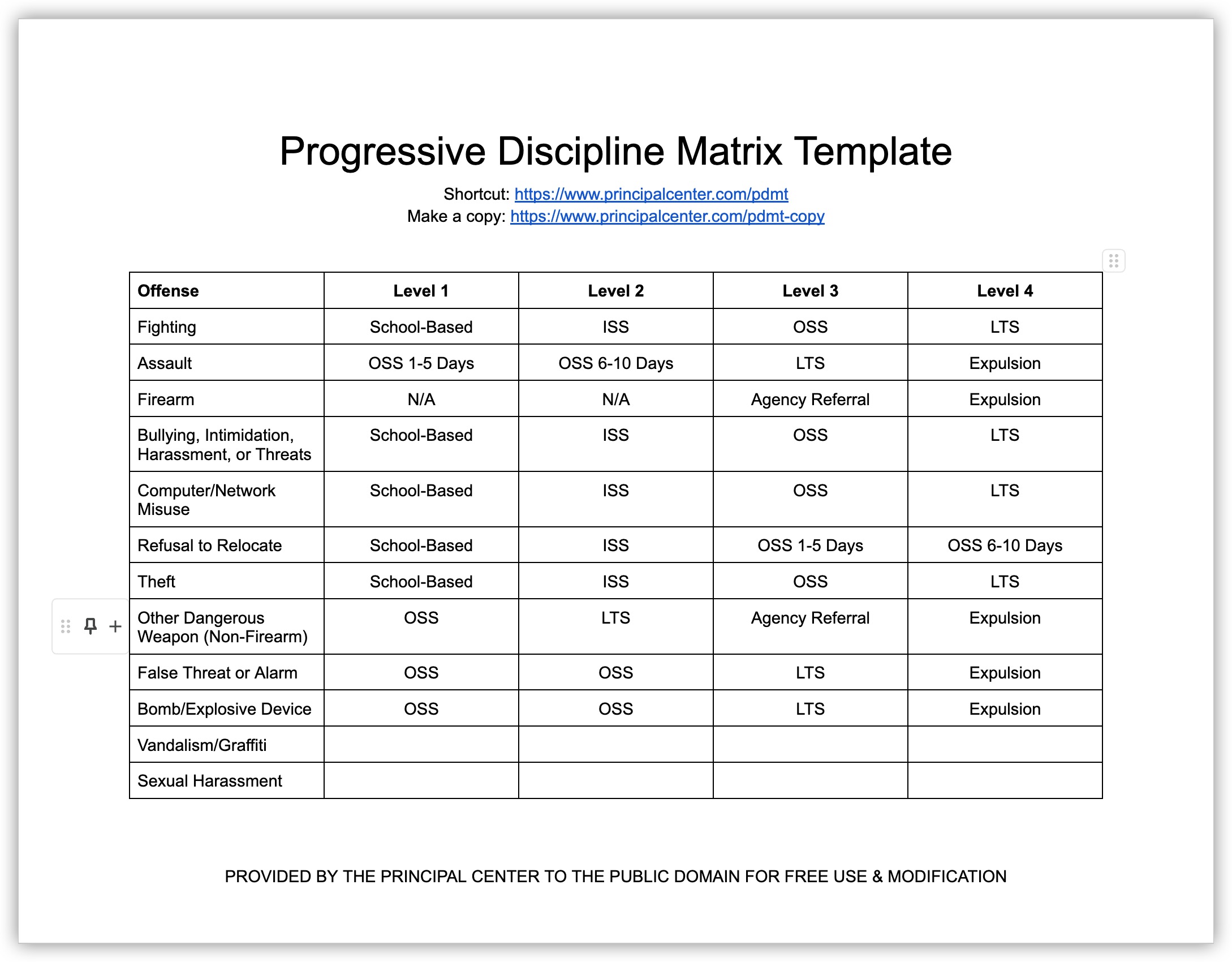

- A Progressive Discipline Matrix (PDM) is a chart of consequences for specific categories of prohibited behaviors, specifying escalating consequences for more severe or repeated misbehavior.

- Predictable consequences for major behaviors are a central component of a credible, defensible system for maintaining safety and order in schools.

- Since schools have a limited ability to change student behavior—especially the most extreme behaviors—a PDM provides a way to uphold boundaries for acceptable behavior without imposing harsh or arbitrary consequences on students who are struggling.

- PDMs are defensible because they are evidence-based—demonstrating that the school is taking sufficient, but not excessive, action in response to student misbehavior.

- Predictable consequences satisfy the needs of numerous stakeholders, including the district, parents, staff, and students.

- A PDM meets district needs by aligning school practices with district expectations and regulatory requirements (e.g. oversight by the US Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights, the Department of Justice, and state regulators).

- A PDM meets the needs of parents by communicating expectations and consequences in advance, reducing conflict and legal action over disciplinary decisions.

- A PDM meets the needs of staff by creating boundaries for behavior—an essential aspect of staff working conditions. A PDM also allows staff to hold administrators accountable for making sound discipline decisions.

- A PDM meets student needs by clarifying both expectations for behavior and consequences for violating these expectations.

- Students benefit from a PDM's clarity about consequences for specific behaviors, which protect them from arbitrary or capricious consequences, and can help them make good decisions about their own behavior.

- A PDM meets the needs of administrators by detailing specific consequences for specific behaviors, offering protection against undue influence by parents or staff.

- Since student behavior is inherently unpredictable, schools cannot ensure absolute safety; some degree of disruption and violence will occur. A Progressive Discipline Matrix (PDM) guarantees procedural safety by creating predictability about the school's response to extreme behavior.

- Staff who work with the most challenging students benefit from knowing that if students engage in severe inappropriate behavior, they will face appropriate consequences.

- Students who have experienced trauma have an even greater need for predictability in the learning environment. A PDM offers reassurance that peers will face appropriate consequences for their actions.

- Testing boundaries is a normal developmental task of adolescence. A PDM ensures humane, reasonable, and predictable responses by school administrators.

- A district's discipline decisions are more legally defensible if they are demonstrably consistent across schools and specific situations.

- PDMs provide school administrators with an appropriate level of guidance, without constraining professional judgment to an unhelpful degree.

- "Zero-tolerance" approaches apply consequences without regard to context, intent, or other factors relevant to discipline. In the 1990s and early 2000s, a number of high-profile cases illustrated the pitfalls of zero-tolerance approaches. In 1999, for example, a student named Tawana Dawson was expelled from Pensacola High School in Florida for bringing nail clippers with a 2-inch nail file "blade" to school.

- Zero-tolerance policies are often presumed to be more legally defensible than policies relying on administrator judgment, but as some legal observers have noted, zero-tolerance policies often result in more lawsuits, and courts are likely to side with parents against administrators who make obviously unreasonable discipline decisions. In practice, zero-tolerance policies are usually applied in a manner more strict and unreasonable than required by law.

- Few zero-tolerance policies are in effect today, in recognition of administrators' need to exercise professional judgment in making discipline decisions.

- On the other extreme, total discretion with regard to consequences makes it difficult for administrators to make defensible discipline decisions. Ad-hoc consequences, with no basis for shared expectations, open administrators to accusations of harshness, leniency, and arbitrariness.

- Bans on out-of-school suspension and other consequences make it difficult for administrators to ensure a safe and orderly learning environment.

- High-quality PDMs share several key features that distinguish them from less clear behavior policies.

- Specificity—specific types of behaviors are associated with specific consequences.

- Escalation—the PDM specifies more severe consequences for repeated or more serious behaviors.

- Flexibility—administrators have the latitude to apply sound professional judgment to each situation.

- Transparency—students, staff, and parents have access to the same criteria administrators are using.

- Accountability—administrators can be held accountable for issuing consequences consistent with the PDM.

- Design features of PDMs

- Behavior categories, e.g. fighting, theft, arson, etc.

- Distinction between classroom-managed and admin-managed behaviors

- Consequences, e.g. conference, detention, Saturday school, ISS, OSS, expulsion

- Differentiation by grade level, e.g. elementary, middle school, high school

- Latitude for administrator discretion based on mitigating & aggravating circumstances

- Progressive steps for repeated incidents

How Discipline Works—And What We Should Not Expect It To Accomplish

- Progressive Discipline (PD) is the only viable approach to school discipline because it protects the rights of students while protecting the learning environment from violence and disruption.

- Every school must have a clear, published discipline matrix specifying consequences for specific categories of behavior, such as classroom disruption, fighting, and assault.

- Consequences need to be "progressive," meaning increasing in severity for repeated or more serious misconduct.

- Administrators must exercise sound professional judgment to make discipline decisions based solely on the school discipline matrix and the facts of the situation, not based on the specific students involved.

- While some students may need differentiated supports, it is not appropriate to differentiate consequences in violation of the school discipline matrix.

- Flexible, ad-hoc approaches to discipline may sound appealing as a way to address individual circumstances, but they have serious drawbacks that make them inappropriate for school discipline.

Exclusionary Discipline

- Schools cannot use truly "natural consequences" to address violent behavior.

- The "natural" consequence for violence is retaliatory violence, which is not an acceptable option in the school environment.

- Violence that is not addressed with exclusion is likely to result in further violence, even if retaliation is prohibited.

- Exclusion is the most humane and "natural" consequence for behavior incompatible with a social environment.

- Violating group norms, such as the rules of a game or sport, naturally results in exclusion from the activity.

- Excluding individuals from an activity they are disrupting is the least severe, yet effective, way of dealing with the disruption without harming the individual.

- Exclusionary discipline, used appropriately, is not harmful.

- Exclusionary discipline protects the learning environment from disruption and violence.

Behavior & Self-Control

- Behavior is a "muscle," not a "skill"

- Skills can be taught, practiced, and improved, but it is an error in category to view behavior as a "skill" per se.

- Controlling one's behavior relies on a number of different executive functions, only a few of which are skills (such as organizational skills).

- Like muscular strength, self-control can be improved despite not being precisely a skill.

- Consequences play an essential role in improving behavior, because they direct effort toward acceptable behaviors.

- Instruction plays only a small role in improving behavior in school, because students largely already possess the knowledge needed to behave appropriately.

The School-To-Prison Pipeline

- The "School-to-Prison Pipeline" (STPP) is a hypothesized causal link between school disciplinary practices and increased risk of incarceration.

- Excessively harsh school discipline practices, such as referring minor behaviors for criminal prosecution, or excluding students from school for long periods of time over minor issues, may plausibly create an STPP effect. However, these practices are increasingly rare, and are easy to identify and eliminate.

- Success in school is generally highly predictive of success in employment, higher education, and other outcomes.

- Virtually all students attend school from an early age—including the small percentage of students who later face incarceration. The "first school, then prison" chronology does not imply a causal relationship.

- Unsurprisingly, research has long found a strong correlation between receiving school discipline and later incarceration, as both are a function of individual behavior.

- Despite many attempts, no studies have demonstrated a causal link between progressive discipline practices and incarceration. The correlation between school-based consequences and incarceration is explained entirely by the common cause of individual behavior.

- Studies of a hypothetical STPP are hampered by the lack of reliable data linking behavior and consequences.

- Most school districts do not systematically collect data on student behavior. In some of the most prominent studies, consequences are used as a proxy for behavior.

- In other studies, data about behavior incidents (such as that collected by NYC DOE) does not distinguish between victims and perpetrators, making it impossible to assess the impact of consequences on later outcomes.

- Efforts to break the STPP that focus on eliminating consequences, rather than reducing behaviors that result in school discipline, are likely to be ineffective while also harming the learning environment.

- There is no evidence that eliminating exclusionary discipline, such as out-of-school suspension, improves students' odds of avoiding incarceration.

Research Review: What Does the Evidence Say?

The School-To-Prison Pipeline Hypothesis

- A great deal of research has examined the correlation between school discipline and negative life outcomes such as earning fewer credits in or graduate from high school, arrest, and incarceration. Not surprisingly, school discipline correlates strongly with other negative outcomes.

- The "School-To-Prison Pipeline" (STPP) is a hypothesized, but unproven, causal relationship between school disciplinary consequences (especially out-of-school suspension, or OSS) and subsequent entanglements with the criminal justice system (e.g. arrest). Whether this relationship is actually causal, not merely correlational, remains unproven.

- Advocates of the school-to-prison pipeline hypothesis have long sought to establish a causal relationship between school disciplinary consequences and negative outcomes, under the assumption that modifying or eliminating such consequences might improve outcomes. However, despite numerous studies, no causal link has been demonstrated, nor have prohibitions against OSS been shown to improve student outcomes.

- Research aiming to establish a causal relationship between school disciplinary consequences and negative outcomes must be designed carefully to distinguish between causation and mere correlation. Many studies suffer from the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy—the assumption that the earlier event caused a subsequent event. Just as a rooster's crow precedes the sunrise but does not cause the sunrise, it is important to distinguish between causal factors and those that merely precede an outcome such as incarceration.

Does Correlation Imply Causation?

- About 35% of students are suspended at some point during their K-12 career. About 50% of students who receive out-of-school suspension are only suspended once, then never again (Shollenberger 2013). This suggests a substantial deterrent effect on both suspended students and peers.

- About 39% of males are arrested at least once by age 28. Fully 25% of males who have never been suspended from school get arrested, but more suspensions are correlated with a greater likelihood of arrest (Shollenberger, 2013). This suggests that while school suspension is strongly predictive of later arrest, the relationship is not causal, but merely a correlation based on the common cause of individual behavior.

- The predictive power of OSS on other outcomes is substantial. Mittleman (2018) states “I estimate that suspended children are two times more likely to experience an adolescent arrest than otherwise similar children.” Shollenberger (2013) found that while 87% of boys who never received OSS graduated from high school, only 64% of those receiving OSS graduated.

A Research Challenge: Lack of Data on Behavior

- One major research challenge in establishing a causal relationship between discipline and outcomes is that STPP studies lack direct measures of an obvious confounder: student behavior. Mittleman (2018) notes that “there are likely to be unobserved factors that govern children’s risk for both suspensions and arrests. If suspensions indicate the crossing of some unmeasured behavioral threshold that divides seemingly similar children, then the suspension itself could still carry few consequences.” Obviously behavior is the primary determining factor in both school discipline and criminal justice.

- Lacking direct data on student behavior, STPP studies use a variety of approaches to isolate the effect of consequences such as OSS. LiCalsi et al. (2021), for example, combined unusually detailed incident records from the NYC Department of Education with separate disciplinary consequence records in an attempt to isolate the effect of consequences. However, the incident data set does not distinguish between perpetrators and victims, establishing a spurious relationship between consequences and other negative outcomes; obviously perpetrators of disciplinary incidents are likely to have worse outcomes than victims.

- Other studies deal with the lack of behavior data by using proxy measures to stand in for unknown quantities. For example, Bacher-Hicks et al. (2021) use a construct they call "school strictness" to attempt to remove behavior from the equation. Not surprisingly, this study reports that "young adolescents who attend [middle] schools with high suspension rates are substantially more likely to be arrested and jailed as adults." However, rather than examine strictness itself—that is, what consequences are given for specific behaviors—"strictness" is assessed based on suspension rate alone, with no direct measure of behavior or how consequences are applied. Clearly, this approach makes it impossible to distinguish the effect of consequences from the effect of behavior on later arrest.

References

Bacher-Hicks, A., Billings, S., & Deming, D. (2021). Proving the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Stricter middle schools raise the risk of adult arrest. Education Next, 21(4), 52-57. https://www.educationnext.org/proving-school-to-prison-pipeline-stricter-middle-schools-raise-risk-of-adult-arrests/

LiCalsi, L., Osher, D., & Bailey, P. (2021). Empirical Examination of the Effects of Suspension and Suspension Severity on Behavioral and Academic Outcomes. https://www.air.org/project/less-more-effects-suspension-and-suspension-severity-behavioral-and-academic-outcomes

Mittleman, J. (2018). A School-to-Prison Pipeline? Exclusionary Discipline and the Production of Delinquency. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/28qk4/

Shollenberger, T. (2013). Racial Disparities in School Suspension and Subsequent Outcomes: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997. http://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/state-reports/racial-disparities-in-school-suspension-and-subsequent-outcomes-evidence-from-the-national-longitudinal-survey-of-youth-1997