By Justin Baeder, PhD

School leaders are always looking for ways to maximize teacher motivation. Yet some of the most eye-catching approaches are counterproductive, undermining the very professional commitments they're intended to bolster.

Fortunately, a large and well-established body of research guides us in how to help teachers feel great about their work and their workplace, so they can do their best for students every day.

In this guide, we'll look at awards, gifts, prizes, and how extrinsic motivators work (or fail to work) more broadly, and we'll examine the factors that maximize teachers' intrinsic motivation.

Motivators vs. Hygiene Factors

Herzberg's Two-Factor Theory divides motivational factors into two distinct categories:

- Motivators, such as important, challenging work; recognition for one's contributions; involvement in decision-making; and so forth.

We typically think of these as “intrinsic” motivators, and leaders play an important role in ensuring that they are in place.

Jen Schwanke's book The Teacher's Principal: How School Leaders Can Support and Motivate Their Teachers is an excellent guide to addressing these factors. - Hygiene factors, such as compensation, job security, and a comfortable workplace, which are demotivating in their absence. Providing them is essential for ensuring that teachers do not become demoralized, but providing extra will not create extra motivation.

For example, someone who is underpaid or has a cramped utility closet for an office may be demoralized by these subpar conditions…yet beyond a given threshold, further improvements will not result in greater motivation. A big-enough workspace is important, but a palatial workspace is not necessarily better.

Leaders who have successfully improved hygiene factors from a subpar level to a satisfactory level may be thrilled at the impact of their efforts, as they've seen demoralization give way to a healthy level of satisfaction with teacher working conditions.

Teachers who've seldom been offered a snack or given a kind word will respond with gratitude to these gestures.

However, doing more of the same will not take staff morale to the next level. After dealing with the problematic hygiene factors, leaders must turn their attention to intrinsic motivators.

Unfortunately, leaders who are unsure how to support intrinsic motivation tend to rely on extrinsic motivators like awards, gifts, and “passes.”

What's Wrong with Extrinsic Rewards?

Extrinsic rewards tend to fall into several common categories:

- Formal awards such as Teacher of the Month or Year

- Occasion-based gifts that may be appreciated, but are not expected or necessary, such as back-to-school, year-end, holiday, and birthday presents

- Contingent rewards, such as prizes given out through programs like Workplace Rewards for Teachers

- Unexpected treats like snacks and drinks, or expected treats for teacher appreciation week

Everyone appreciates snacks, treats, and efforts to show appreciation in general, but leaders must exercise great caution when it comes to awards, gifts, and contingent rewards.

Writing in Harvard Business Review three decades ago, Alfie Kohn argues:

According to numerous studies in laboratories, workplaces, classrooms, and other settings, rewards typically undermine the very processes they are intended to enhance. The findings suggest that the failure of any given incentive program is due less to a glitch in that program than to the inadequacy of the psychological assumptions that ground all such plans.

Alfie Kohn, “Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work,” Harvard Business Review, Sept/Oct 1993

The Professional Norms That Make Teachers Uncomfortable with Awards

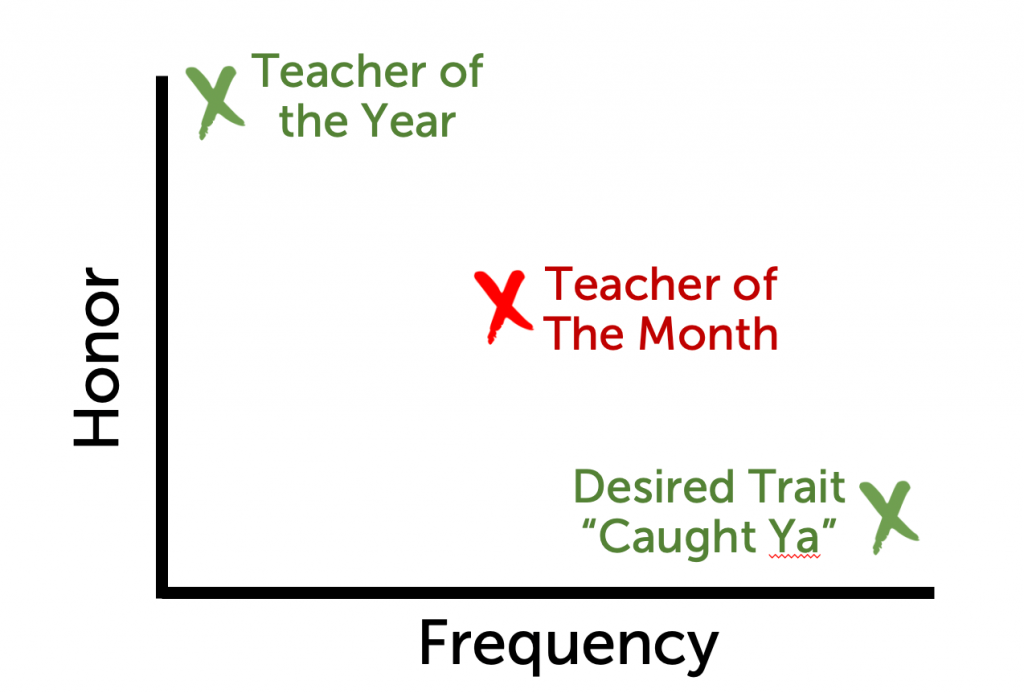

One obvious and popular form of extrinsic motivation is awards, such as teacher of the month, teacher of the year, or more frequent awards recognizing specific attributes.

While awards can be an effective way to reinforce desired traits, they run the risk of violating strong professional norms of egalitarianism and collaboration, so caution is in order, and it's worth distinguishing between several types of awards.

Let's consider two properties of an award: frequency and honor. The best awards tend to be high-frequency and low-honor, or vice-versa, while avoiding the danger zone in between.

For example, FranklinCovey's Leader In Me program encourages schools to recognize staff members with “Lighthouse Leader” awards, noting specific attributes they exemplify, such as “putting first things first.” Schools may issue a dozen or more of these awards per month to teaching and non-teaching staff.

When I was a middle school teacher, my principal made a point of listing all the “above and beyond” contributions people made in her newsletter each week. While there was no reward attached to this form of recognition, it was powerful and appreciated.

Such awards are designed to “catch” people exemplifying desired traits in order to reinforce them for everyone, rather than to incentivize the individual. These awards tend not to violate egalitarian norms, especially if large numbers are given out and everyone receives them eventually.

On the other extreme, many schools and districts recognize a Teacher of the Year, which is typically a high honor that not everyone expects to receive.

While this type of award also serves the collective purpose of holding up exemplary practice for all to see, the individual honor is much greater, and can spark jealousy or embarrassment. Teachers may be mortified to be singled out from their colleagues, whom they may feel deserve equal recognition.

Nevertheless, it may be worth the risk, since it provides a rare opportunity to spotlight individual excellence.

In between these two ends of the spectrum are more frequent formal awards such as Teacher of the Month, which fall in murky territory, so caution is in order.

Teaching is professional work, and “Employee of the Month” awards in other organizations are typically not given to professional-class workers. For example, retail fast food, and other service-industry jobs are among the most common roles to receive this type of award.

Physicians, attorneys, computer scientists, and engineers would look askance at an Employee of the Month award. Bored Teachers, ever a fount of unfiltered educator opinion, goes so far as to claim they destroy morale (while offering ill-conceived advice to give out “passes,” which we'll discuss below).

Educators who have shared their experience with Teacher of the Month awards have noted the perception that such awards are used to reward loyalty and play favorites, and encourage “kissing up” behavior such as spending excessive time in the office to remain on the principal's radar.

For these reasons, it's best to stick with high-frequency, low-honor forms of recognition that reinforce specific attributes, and low-frequency, high-honor awards like Teacher of the Year, and avoid the murky middle of Employee of the Month.

Next, let's talk about gifts, which leaders may feel compelled to give at various times of year.

People Don't Know How To Feel About Gifts At Work

Gifts are a normal part of our interactions with friends and family. We're used to buying holiday and birthday gifts for those we hold dear.

It's understandable, then, that school leaders would seek to express their fondness and appreciation for faculty by purchasing gifts, for occasions such as:

- Back-to-school time

- The holidays

- Individual staff birthdays

- Teacher appreciation week

- The end of the school year

- New hires and retiring staff

However, gifts are for friends and family, not employees.

A “gift” from employer to employee is part of an employment arrangement, not simply a nice gesture. Remember Clark Griswold's feelings about the Jelly of the Month Club in Christmas Vacation?

Because gifts are not a normal part of workplace interactions between supervisor and employees, they can make teachers uncomfortable, raising questions such as:

- Was I supposed to buy my administrator a gift, too? Do I look like a jerk now?

- Why did we all get the same thing? Was I supposed to appreciate this piece of one-size-fits-all junk?

- Why didn't we all get the same thing? Is my administrator playing favorites?

- How did you have time to make all these gifts, when you're constantly complaining about how busy you are?

- Buying all this must have cost you a fortune. Is this a pathetic attempt to make up for something terrible, like the cheating husband who buys his wife a nice piece of jewelry?

- 20 years of service, and this is all I get?

Gifts are for friends and family. While our co-workers are often our friends too, gift-giving in the context of a supervisory relationship is fraught with danger of hurt feelings, and is best limited to whole-staff gifts.

Since gifts are costly in terms of time and money, and often make people feel uncomfortable, some leaders have attempted to use “passes” and other contingent extrinsic rewards to motivate and recognize staff.

This, too, is fraught with risk.

Contingent Rewards Are Insulting To Professionals

The education profession has a storied history of attempting to use contingent rewards with teachers.

Merit pay has been repeatedly tried—without much success. By and large, teachers do not want to be paid more for producing higher student test scores.

They want to be paid fairly, and given the opportunity to do their best work, without the distorting pressures of high-stakes test scores.

Contingent extrinsic rewards take this same idea and bring it down to the level of behavior. If administrators can reinforce specific teacher behaviors, the thinking goes, teachers will focus more energy on those behaviors, leading to desired changes in practice.

However, contingent rewards go against established, but often unspoken, professional norms, as well as a great deal of established research, which is summarized at length in Alfie Kohn's definitive Harvard Business Review article.

No teacher would say “I'll only teach well if you give me candy.” Many teachers like candy, and might appreciate it under normal, no-strings-attached circumstances. But giving teachers candy for teaching well implies that they wouldn't do it without the candy.

It turns a pleasant surprise into an unsatisfying—even insulting—form of compensation.

Giving the choice between contingent rewards and better baseline conditions for everyone, educators almost always choose the latter.

Teachers nearly always choose higher, more equal compensation for everyone over individualized, performance-based merit pay, even if they'd individually benefit more from the latter.

Imagine asking your staff: “Would you like me to bring you a donut when you get your attendance done on time, or would you just like me to get donuts and put them in the staff lounge once in a while?”

You know the answer.

Extrinsic rewards ring the wrong bell for professionals—a pavlovian bell that belongs in the world of animal training, not K-12 education.

Nearly all educational leaders would shudder if a teacher said “I give my students candy for good grades on their tests. The more they learn, the more candy I give them.”

We know this over-reliance on extrinsic motivation is wrong. So we must stop modeling it, and stop subjecting teachers to the same kinds of reward systems we wouldn't want them to use with students.

This includes not just treats or monetary rewards, but privileges, too.

Why “Passes” Undermine Professional Culture

A popular type of incentive is the “pass,” which gives teachers the one-time privilege of getting out of something they're normally required to do, such as:

- Jeans passes, which exempt the teacher from a dress code that normally doesn't allow jeans

- Flip flop pass—like a jeans pass for your feet

- Team jersey day—the teacher can wear their favorite sport's team's jersey in lieu of otherwise-required professional attire

These types of passes may seem innocent enough, but they raise an important question:

If it's OK to make an exception to the rule…why have the rule in the first place?

Teachers may appreciate the flexibility a “pass” provides, and many school leaders report that teachers are enthusiastic about the idea—even choosing jeans passes from among a variety of options for recognition.

But if teachers can use a pass to wear jeans without any negative consequences for student learning, professional climate, or other important outcomes…why not allow jeans all the time?

Or, in contexts where jeans are considered unprofessional…does a jeans pass undo the damage to one's credibility with students and parents?

Teachers quickly realize what's going on: they have been arbitrarily restricted from doing something that would actually be fine, so it can be doled out selectively as a privilege.

Viewed in this light, “passes” aren't a form of appreciation or recognition.

They're a form of manipulation, in which something basic and expected is cynically transformed into a reward by withholding it and making it contingent.

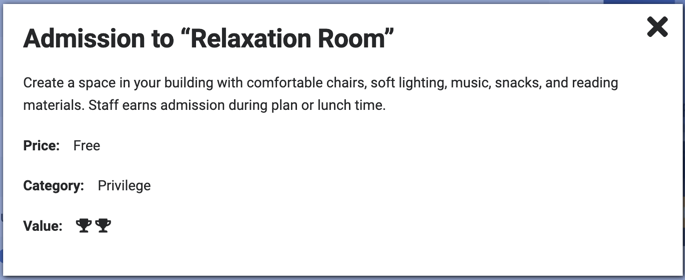

That's what especially bothers me about this reward suggested in this Ultimate List of Teacher Incentives:

Let's be honest: most staff lounge spaces could use a serious upgrade. Providing:

- Comfortable seating that isn't full of stains

- Soft lighting instead of cold fluorescent tubes

- Relaxing music

- Free snacks and good drinks

…and other amenities would be appreciated by any staff. But hold on: why should teachers have to earn admission?

Corporate America has long recognized the value of providing fun, comfortable, relaxing spaces for employees to de-stress during the work day. It's hard to imagine Google coders or State Farm reps having to accrue points to earn the right to use the foosball table.

If teachers are professionals, they deserve to be treated as professionals all the time, not given normal workplace amenities as special “treats” that are otherwise restricted.

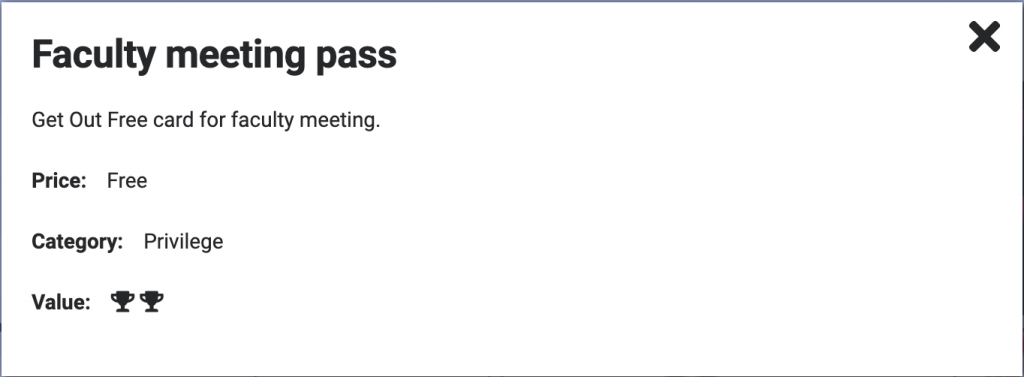

But I've saved the best for last—there's one more type of pass that you may have to see for yourself to believe—the “get out of a faculty meeting” pass:

I wish I was making this up, but apparently this is a real thing that schools are giving out as a reward for teachers.

Let's stop and think for a moment:

- What could make up for the professional learning and collaboration the teacher misses when using a faculty meeting pass?

- If there's a viable answer to the previous question…why are we even having a meeting?

- What message does allowing some people to skip a meeting send to everyone who still has to attend it?

- What message does it send to those facilitating the meeting?

In all of these “pass” examples, the original rationale for the expectation is undermined, and violating the expectation is treated as a privilege rather than a professional misstep.

That's not to say there aren't any good uses for passes; for example, covering an extra duty here and there might be greatly appreciated.

But anything that can be done with a “pass” can be done simply as a professional courtesy or act of kindness. It doesn't have to be doled out as a contingent reward.

Contingent rewards put the teacher in the role of an animal, and the administrator in the role of an animal trainer. We can do better.

Why Some Staff Seem To Appreciate Rewards While Others Are Insulted

If extrinsic rewards are such a bad idea, why are they so popular? Why do teachers so frequently report being thrilled about a jeans pass or a candy bar?

The answer lies in the contrast: extrinsic rewards are popular with many teachers because they're better than nothing.

If you're used to being left out of important decisions, overworked, ordered around, and unappreciated, any small token of appreciation means the world.

So if you're providing these tokens of appreciation for your staff, don't feel bad. Know that you are improving people's lives, and giving them hope that things will continue to get better.

But let's not stop at passes and snacks. Let's give teachers the autonomy they crave and need to do their best work and enjoy a strong sense of intrinsic motivation.

Then, we won't need to worry about relying on extrinsic motivators that can have unintended consequences.

Self-Determination Theory

One of my favorite lenses for viewing educator motivation is Self-Determination Theory, which links intrinsic motivation to three main factors:

- Autonomy

- Competence

- Relatedness

Understanding the nature of teaching as professional work means understanding that teachers need a considerable degree of autonomy to do their work well, given that teaching requires professional judgment under rapidly changing circumstances.

Teachers who have been micromanaged may appreciate a soft drink or a chance to wear flip-flops, but what they really need is the autonomy befitting their role.

They deserve clear expectations and the support to grow as professionals, so they can feel competent at increasingly challenging, sophisticated, and cutting-edge practices.

And they need to be involved in decision-making, so they can truly feel like professionals who have a voice in important matters relating to the functioning of the school.

Yes, it's easier to buy candy.

It's easier to give out jeans passes.

But if you want to motivate your staff, focus on the intrinsic factors (and fix the hygiene factors that need fixing).

Further Reading:

Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work, by Alfie Kohn—Harvard Business Review