Great teaching can't be micromanaged. Here's how to improve practice by developing teacher autonomy.

by Justin Baeder, PhD

When people talk about instructional leadership, they're often talking about one specific practice: giving feedback.

The conventional view is that leaders give feedback, and teachers implement it.

But is this the right paradigm for the relationship between teachers and leaders? Are leaders the instructional decision-makers, and teachers only the implementers?

No.

Too often, when we give feedback, we unwittingly deprive teachers of the autonomy and agency they need.

Why Teachers Need Autonomy

Fundamentally, teachers need autonomy because they are doing professional work that requires professional judgment, and this judgment cannot be exercised without some degree of autonomy.

Teachers make thousands of decisions a day—far too many for even the most dedicated micromanager to handle. Teaching is complex, cognitive work carried out in a dynamic environment full of young people who cannot be taught by teachers who are merely compliant.

Figuring out how to best meet students' needs requires professional judgment that must be exercised by the teacher in real time. Autonomy is absolutely essential.

Of course, not all autonomy is good or necessary.

Teachers may exercise inappropriate forms of autonomy in violation of shared agreements and expectations. For example, a teacher in a phone-free school who lets students play on their phones after they finish classwork does not need or deserve the autonomy to violate school policy.

Standards and curriculum also impose legitimate constraints on teacher autonomy:

- Algebra teachers don't have the discretion to skip quadratic equations

- A US History teacher doesn't need the autonomy to spend half the year on ancient Egypt

- A teacher who moves to 4th grade can't teach the same material she used with 2nd graders

As educators, we have defined degrees of autonomy over various areas of practice.

We recognize that teachers are not independent practitioners who enjoy full autonomy over every aspect of their work—especially what they teach and whom they teach. Teachers are hired to teach specific classes, with standards and students they don't choose.

Most notably, teachers need autonomy over how they teach, and how they address the thousands of decisions they face each day in the classroom. Mandates and micromanagement are no substitute.

Specific forms of autonomy are essential for doing the professional work of teaching, but teacher autonomy should not be treated as a solution to inadequate resources.

Autonomy Is Not An Excuse for Inadequate Resources and Support

Teacher autonomy is necessary, but it's not a solution to every problem.

Too often, autonomy is weaponized and used as an excuse for failing to provide appropriate resources and support.

Imagine telling a custodian “You have full autonomy to choose your own cleaning supplies and tools.”

“But where are the mops?” might be the reply.

Obviously, schools are expected to provide mops and cleaning supplies, and custodial “autonomy” is no excuse for failing to do so.

Asking a custodian to select the best tools for the job is one thing. Failing to provide them is another.

Too often, we treat teacher autonomy as the solution to inadequate organizational investment in essential resources and support.

Curricular materials are often under-specified and poorly resourced, so teachers are frequently left to determine how to teach the standards on their own—not just by making day-to-day teaching decisions, but by obtaining or developing materials from scratch.

Let's examine the issue of curricular autonomy in more detail.

The Curricular Autonomy Conundrum

Teacher autonomy over curricular materials is appealing to both teachers and the organizations they work for:

- It's appealing to teachers because it gives them control over a key aspect of their work, and allows them to exercise creativity and professional discretion

- It's appealing to schools and districts for less noble reasons—because it does not require them to provide materials or training, nor must they bear any responsibility for their quality

Instructional leaders must not only ensure that teachers have the resources and support they need, but also tailor their feedback to domains in which teachers have autonomy.

Once, as a new principal, I observed a sequence of activities in a first-grade math lesson that seemed rather disjointed. Why, I wondered, did the teacher spend time on several unrelated concepts in one lesson?

I was unsure how to approach the feedback conversation with the teacher. Should I suggest focusing on one concept per lesson, rather than jumping between different concepts?

Thankfully, the teacher wasn't going to have any free time to chat for nearly an hour, so I went on to another first grade classroom and gained some additional perspective.

The second teacher was teaching the same lesson in the same way as the first teacher—transitioning quickly between a variety of activities teaching different concepts. And I soon discovered why.

The answer turned out to be curriculum: our new math curriculum featured a “spiral” design in which concepts were introduced gradually, and practiced repeatedly over time through various games and activities. Each lesson thus focused on several concepts and activities, rather than a single concept taught to mastery.

I realized I had narrowly avoided a serious misstep as a new principal: giving feedback on an area of practice in which teachers did not have any autonomy.

Prior to my arrival as principal, teachers had been trained to “trust the spiral” and follow the curriculum with fidelity to ensure that students had a chance to develop their understanding over time as they returned to each concept over and over.

With this in mind, I was able to focus our feedback conversations on more relevant issues, rather than curricular choices that were outside the purview of the individual teacher.

The degree of autonomy teachers have over curriculum varies greatly from district to district, school to school, and even subject to subject. For example, while nearly every elementary school has a common math curriculum—likely one that's used district-wide—most arts and elective teachers have far more autonomy over curricular materials.

The key for instructional leaders is to focus feedback conversations on areas of practice where teachers have a meaningful degree of autonomy. Focusing on professional judgment in domains of autonomy is our best way to have a long-term impact on teacher practice.

Short-term second-guessing won't get us very far—but neither will ignoring practice in a misguided effort to respect teacher autonomy.

The Micromanagement Matrix

Most teachers are left alone most of the time—no other adults see them teach, and no other adults provide feedback on their teaching. For the most part, nobody knows what they're doing from day to day.

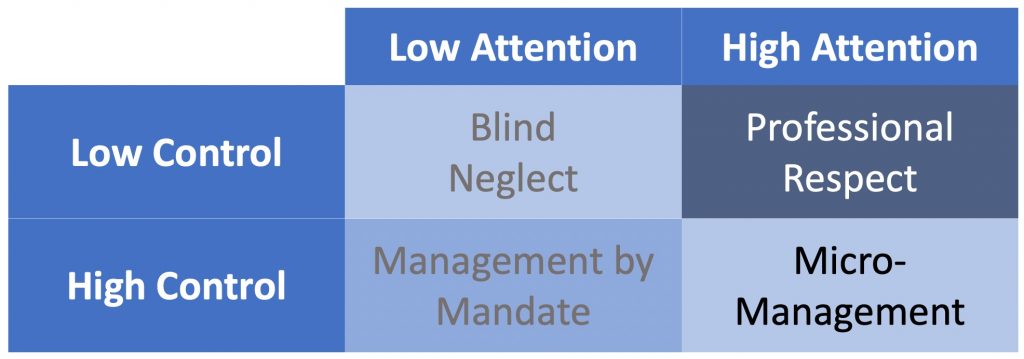

When school and district leaders avoid classrooms and avoid talking openly with teachers about practice, we might label their approach blind neglect.

When an administrator, coach, or other instructional leader does happen to observe and give feedback, it's often in the form of fairly blatant micromanagement:

- The leader, not the teacher, decides what to focus on

- The leader, not the teacher, decides how the teacher's practice should change

Telling people what they're doing wrong and what they should do differently is not an approach to feedback that develops professional judgment. It's sometimes necessary—for example, when people are engaged in unsafe or unethical conduct, or failing to meet basic expectations like taking attendance.

But micromanagement is no way to grow professionals.

These two extremes—neglect and micromanagement—reflect extreme degrees of control and attention:

Read: Instructional Leadership Without Micromanaging

A third possibility is to ignore what teachers are actually doing, while attempting to control it through detailed requirements, which we might call management by mandate.

For example, a principal who requires teachers to submit detailed lesson plans, but never reads them or visits classrooms, is managing by mandate.

Mandates are obviously limited in their ability to meaningfully impact teacher practice, but they have some “advantages” over micromanagement:

- It takes less effort to issue a mandate than to actually work with people

- Leaders who don't know or care how it's going don't have to address any of the challenges and dilemmas people may face as they strive to implement the mandate

But if we're serious about instructional leadership, none of these options are good enough.

We must choose the 4th option, professional respect, and define instructional leadership in a way that recognizes the importance of teacher autonomy and professional judgment.

So what is “instructional leadership”?

A Definition of Instructional Leadership

Instructional leadership is the practice of making and implementing operational and improvement decisions in the service of student learning.

Formal leaders like principals obviously have a role to play in making decisions, but teachers do, too.

In our forthcoming book Cultivate & Activate: Building Capacity for Instructional Leadership, Keith Fickel and I argue that teacher leadership is a legitimate form of instructional leadership, and that the people closest to the work—the teachers who will be implementing decisions—should play a role in making those decisions.

What implications does this have for feedback conversations?

It means we should be willing to empower teachers to call the shots rather than treat feedback as a one-way street.

Phrases like “giving feedback” can imply that what teachers need is some form of constructive criticism, often coupled with reassuring compliments. The “feedback sandwich” is a common format for constructive criticism, though it's not based on any research:

- A compliment about something the teacher did well

- A suggestion or directive for improvement, and

- Another compliment to end on a high note

Does this type of feedback actually change practice, though?

It can, under two specific circumstances:

- The teacher is doing something harmful, and needs to stop

- The teacher is failing to do something essential, and needs to start

In such cases, it's appropriate to give directive feedback, aimed at immediately changing the teacher's behavior:

“You must not scream or yell at students. Instead of yelling, use a consistent signal to get everyone's attention, then give directions in a normal speaking voice.”

It would be a waste of time to ask reflective questions when you already know what you want the teacher to do. No need to play games and make the teacher guess what you're thinking.

Nor is there any need to pay lip service to autonomy in such cases.

But often, the teacher's behavior is fine. It's their thinking—the cognition and decision-making behind their actions—that you want to help improve.

The compliment / suggestion / compliment format is not helpful for enhancing professional judgment.

Instead, have a real conversation that shows professional respect for the teacher as a professional who is doing professional work.

You can simply ask a reflective question:

“I noticed that you asked a series of questions during the discussion that gradually moved to the higher levels of Bloom's Taxonomy. What are you seeing in students' responses to these these higher-order questions, and how does that shape your subsequent questions?”

In other situations, you may not have any feedback about what the teacher could do differently, and you might instead elicit ideas about support and resources.

Think of these reflexive feedback conversations like asking the custodian about mops—when you actually intend to provide what the custodian requests.

A commitment to providing the tools necessary to do the job can be paired with openness to input, treating teachers as serious instructional decision-makers:

“It seems like it's been hard to fit in the anti-bullying lessons between the literacy block, math block, recess, and everything else. What have you tried, and what are your thoughts on what we should do?”

I took this approach with a team of veteran kindergarten teachers who were struggling to find time to teach a mandated anti-bullying program. Rather than direct them to try harder and get it done, I asked what they needed.

Their solution was simple: move recess. I hadn't even considered this possibility, since they normally went to recess with first grade, and moving first grade recess was not an option.

Instead, they proposed going to recess with 5th grade—their “buddy” classes. This would give them a 25-minute block of time between specials and recess—perfect for teaching the anti-bullying lessons.

When we respect teachers as professionals, we discover that they often have better ideas than we do, because they're closer to the work.

What Needs To Change?

To differentiate your approach for each teacher, consider what needs to change.

If the teacher's behavior needs to change immediately, use directive feedback to set expectations.

If your goal is to improve professional judgment, rely on conventional reflective questions. Here are 10 open-ended questions you can use to cite specific evidence, then get the teacher talking.

If your goal is to improve the resources and support you provide for teachers, you can ask a reflexive question to solicit their ideas:

- What do you need from me? How can I support you?

- What would make this a sustainable change?

- How could we get better results as a system?

You can switch dynamically between these types of questions even in a single conversation.

To learn more, read about the three roles we can play in this article: How Instructional Leaders Change Teacher Practice.

Showing Professional Respect for Teacher Practice

Ultimately, we can't ignore or micromanage teacher practice if we want it to improve.

We must be willing to get into classrooms and have conversations with teachers.

When our questions are open-ended and curious about the work teachers are doing, we can avoid the pitfalls of micromanagement as well as blind neglect, and show professional respect.

Office-based activities like analyzing data and planning professional development are important, but they're no substitute for actually seeing teachers at work, and talking with them about their work.

My book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership is all about making a daily habit of classroom visits.

Once- or twice-annual formal observations aren't enough. The more time you spend in each teacher's classroom, the more you'll be able to provide accurate and helpful directive feedback to teachers who are struggling.

As I explain in Chapter 2 of Now We're Talking, the best classroom visits have seven key features:

- Frequent—Approximately once every two weeks

- Brief—Five to ten minutes of observation, followed by a brief conversation

- Substantive—More than just making an appearance

- Open ended—Focused on the teacher’s thinking, not filling out a form

- Evidence based—Centered on what actually happened during the observation

- Criterion referenced—Linked to a shared instructional framework

- Conversation oriented—Designed to lead to reflexive feedback conversations between teachers and instructional leaders

For ten evidence-based questions to structure your conversations with teachers, download the free PDF guide, 10 Questions For Better Feedback On Teaching

To get started quickly and build a sustainable habit of daily walkthroughs, take the Instructional Leadership Challenge and get all of our best tools:

Want to get into classrooms daily? Take the Instructional Leadership Challenge »

Have other questions? Leave a comment.

Leave a comment below if you have other questions about instructional leadership.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership.

A former principal in Seattle Public Schools, he is creator of the Instructional Leadership Challenge, which has helped more than 10,000 school leaders in 50 countries around the world:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for school improvement

Dr. Baeder is the author of Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, and the co-author, with Heather Bell-Williams, of Mapping Professional Practice: How to Develop Instructional Frameworks to Support Teacher Growth (Solution Tree).

He is the host of Principal Center Radio, a podcast featuring education thought leaders, and the founder of Repertoire, the professional writing app for instructional leaders.

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy Studies from the University of Washington and an MEd in Curriculum & Instruction from Seattle University, and is a graduate of the Danforth Program for Educational Leadership at UW.